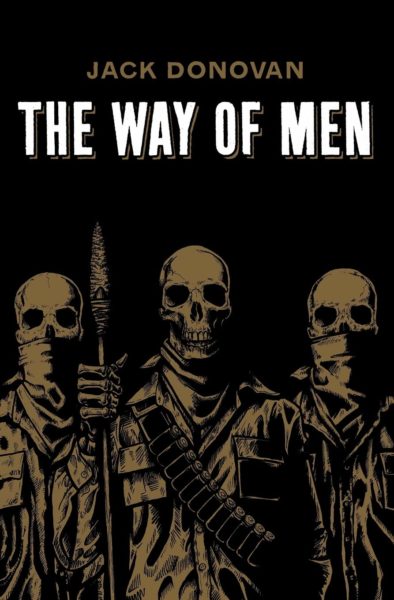

These highlights are from the Kindle version of The Way of Men by Jack Donovan.

When someone tells a man to be a man, they mean that there is a way to be a man. A man is not just a thing to be—it is also a way to be, a path to follow and a way to walk.

The women whom men find most desirable have historically been attracted to—or been claimed by—men who were feared or revered by other men. Female approval has regularly been a consequence of male approval.

Humans are mammals, and like most mammals, a greater part of the reproductive burden will fall on women. That’s not fair, but nature isn’t fair.

The human brain can only process enough information to maintain meaningful relationships with 150 or so people at any given time.

If you put males together for a short period of time and give them something to compete for, they will form a team of us vs. them. This was famously illustrated by Muzafer Sherif’s “Robbers Cave Experiment.” Social psychologists separated two groups of boys and forced them to compete. Each group of boys created a sense of us based on what they liked about themselves or how they wanted to imagine themselves. They also created negative caricatures of the other group. The groups became hostile toward each other. However, when the researchers gave them a good enough reason to cooperate, the competing gangs were able to put aside their differences and join together in a larger party.

Epics and action movies translate well because they appeal to something basic to the male condition—a desire to struggle and win, to fight for something, to fight for survival, to demonstrate your worthiness to other men.

Men who have more muscle tend to have and maintain higher testosterone levels, and men who have higher testosterone levels tend to have an easier time getting bigger and stronger.

Men aren’t wired to fight or cooperate; they are wired to fight and cooperate.

Men who have more muscle tend to have and maintain higher testosterone levels, and men who have higher testosterone levels tend to have an easier time getting bigger and stronger.

Strength is the ability to exert one’s will over oneself, over nature and over other people.

It does not take courage to use strength to pick up a glass and lift it to your mouth. Courage implies a risk. It implies a potential for failure or the presence of danger. Courage is measured against danger. The greater the danger, the greater the courage.

We can acknowledge, as Aristotle and the Romans did, that courage in its highest and purest form involves the willful risk of bodily harm or death for the good of the group.

Before we can have a willingness to take risks for the group—call that “high courage”—we must also possess some kind of “low courage” that amounts to a comfort with risk-taking. Risk-taking comes more naturally to some than to others, and it comes more naturally to men than it does to women. As strength is trainable, so is courage. But like strength, some have a greater aptitude for risk-taking than others.

When there is no heroic objective in sight, boys will dare each other to do all sorts of stupid things. However, a male who is comfortable with low risk taking is likely going to be surer of himself—and more successful—when the time comes to take a heroic risk.

It is not the strongest man who will necessarily lead, it is the man who takes the lead who will lead.

Courage is the will to risk harm in order to benefit oneself or others.

One of the problems with massive welfare states is that they make children or beggars of us all, and as such are an affront and a barrier to adult masculinity.

Mastery is a man’s desire and ability to cultivate and demonstrate proficiency and expertise in technics that aid in the exertion of will over himself, over nature, over women, and over other men.

In a cosmopolitan scenario where frequent travel, fleeting connections and temporary alliances are the norm, the us vs. them never quite takes shape on the direct interpersonal level. Instead, the honor group is ritualized or metaphorical—as with sports teams and political parties and ideological positions.

Honor is a man’s reputation for strength, courage and mastery within the context of an honor group comprised primarily of other men.

Because masculinity and honor are by nature hierarchical, all men are in some way deficient in masculinity compared to a higher status man.

The flamboyantly dishonorable man seeks attention for something the male group doesn’t value, or which isn’t appropriate at a given time.

Thinking men ask “why.” It’s not always enough to win. Men want to believe that they are right, and that their enemies are wrong. To separate us from them, men find moral fault in their enemies and create codes of conduct to distinguish themselves as good men.

In Shakespeare’s The Life of Henry the Fifth, the King promised his enemies that unless they surrendered, his men would rape their shrieking daughters, dash the heads of their old men, and impale their naked babies on pikes. Today, if a military leader made a promise so indelicate, he would be fired and publicly denounced as an evil, broken psychopath. I can’t call Henry an unmanly character with a straight face.

Insulting a man’s honor—his masculine identity—is a good way to test him. It’s a good way to get his blood up. It’s a good way to pick a fight.

Men of ideas and men of action have much to learn from each other, and the truly great are men of both action and abstraction.

Being good at being a man isn’t a quest for moral perfection, it’s about fighting to survive. Good men admire or respect bad men when they demonstrate strength, courage, mastery or a commitment to the men of their own renegade tribes. A concern with being good at being a man is what good guys and bad guys have in common.

A man who is more concerned with being a good man than being good at being a man makes a very well-behaved slave.

Rome was founded by a gang, and it behaved like a gang. To paraphrase St. Augustine, it acquired territory, established a base, captured cities, and subdued people. Then it openly arrogated itself the title of Empire, which was conferred on it in the eyes of the world, not by the renouncing of aggression but by the attainment of (temporary) impunity.

Rome was founded by a gang, and it behaved like a gang. To paraphrase St. Augustine, it acquired territory, established a base, captured cities, and subdued people. Then it openly arrogated itself the title of Empire, which was conferred on it in the eyes of the world, not by the renouncing of aggression but by the attainment of (temporary) impunity.

The story of Rome is the story of men and civilization. It shows men who have no better prospects gathering together, establishing hierarchies, staking out land and using strength to assert their collective will over nature, women, and other men.

The repudiation of violent masculinity is the murder of male identity.

The goal of civilization seems to be to eliminate work and risk, but the world has changed more than we have. Our bodies crave work and sex, our minds crave risk and conflict.

In the future that globalists and feminists have imagined, for most of us there will only be more clerkdom and masturbation. There will only be more apologizing, more submission, more asking for permission to be men. There will only be more examinations, more certifications, mandatory prerequisites, screening processes, background checks, personality tests, and politicized diagnoses.

The true “crisis of masculinity” is the ongoing and ever-changing struggle to find an acceptable compromise between the primal gang masculinity that men have been selected for over the course of human evolutionary history, and the level of restraint required of men to maintain a desirable level of order in a given civilization.

Civilization comes at a cost of manliness. It comes at a cost of wildness, of risk, of strife. It comes at a cost of strength, of courage, of mastery. It comes at a cost of honor. Increased civilization exacts a toll of virility, forcing manliness into further redoubts of vicariousness and abstraction. Civilization requires men to abandon their tribal gangs and submit to the will of one big institutionalized gang.

Strength requires an opposing force, courage requires risk, mastery requires hard work, honor requires accountability to other men. Without these things, we are little more than boys playing at being men, and there is no weekend retreat or mantra or half-assed rite of passage that can change that.

Men must have some work to do that’s worth doing, some sense of meaningful action. It is not enough to be busy. It is not enough to be fed and clothed given shelter and safety in exchange for self-determination. Men are not ants or bees or hamsters. You can’t just set up a plastic habitat and call it good enough. Men need to feel connected to a group of men, to have a sense of their place in it. They need a sense of identity that can’t be bought at the mall. They need us and to have us, you must also have them. We are not wired for “one world tribe.”

The conclusion I reached while writing this book was that the gang is the kernel of masculine identity. I believe it is also the kernel of ethnic, tribal, and national identity. The culture of the gang is, as author bell hooks wrote in a rather different context, “the essence of patriarchal masculinity.”

Gang – A bonded, hierarchical coalition of males allied to assert their interests against external forces.