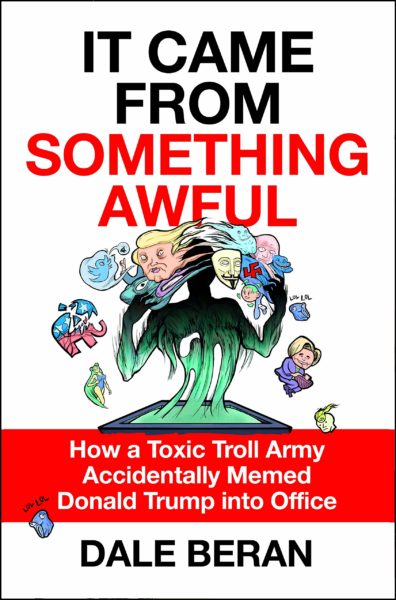

These highlights are from the Kindle version of It Came from Something Awful: How a Toxic Troll Army Accidentally Memed Donald Trump into Office by Dale Beran.

As the microphone was passed from rubber dinosaur to trench-coat mafia kid to sea witch to ask their curly-headed leader questions, the teens/monsters kept debating and joking about things called “memes” and “trolls.” In the mid-2000s, these terms were meaningless to anyone outside that room. But later they broke out of it and saturated every inch of the world.

When 4chan began it wasn’t all that different from other online message boards; it was a place to post content and talk to people on the internet. At the time, it imported a few innovations from Japanese sites, which accounted for some of its popularity. It was easy to post images. And following a Japanese custom, it didn’t require the user to sign up for an account. Anyone could post under a default name, which eventually became the name of all 4chan users, “Anonymous.”

How did a pornographic anime website transform from a postcultural garbage heap into the postcultural garbage heap upon which the great events of our age stood? That story is the story of this book.

Many fake 4chan conspiracy theories had turned into political causes: gamergate in 2014 and pizzagate in 2016. And just a few years prior to that, 4chan had spawned an international far-left hacktivist collective called Anonymous, which had played a role in Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring.

As late-60s counterculture struggled with the burden of infinite choice in postwar plenty, manufacturers were struggling with the same problem: If all the basic needs of human beings were met, yet the factories were still running, how would they get people to buy their products? The solution they came up with was to manufacture need. As American capitalism transitioned from selling products as practical necessities to products as gateways into ideals, aspirations, and joys, counterculture was employed as the advertisers’ most powerful tool.

When my father was in his early twenties, he escaped from behind the Iron Curtain hidden beneath camping gear in the back seat of a Morris Mini Minor, a Nazi Luger pressed against his chest. When he reached the freedom of the West without having to fire it, his first act as a Westerner was to dismantle the gun and throw the pieces into a lake. He always ended the tale that way, proudly concluding that “the pieces are probably still there, rusting away at the bottom of that lake.”

The Nazis, the Communist partisans, Stalin’s spies, the SS—the men had all died, but they weren’t dead, only sleeping. The factions would come again, and angry that he had bested them, take revenge for old grievances.

One of the books that sparked the countercultural revolution, Herbert Marcuse’s 1964 One-Dimensional Man, happened to be on the subject of societal expectations and calibrating one’s own sense of inner gratification.

Contemporary socialist philosopher Slavoj Zizek often uses the example of the word “Enjoy!” stamped on cans of Coke. At first glance, “Enjoy!” reads as an invitation to indulge. But beneath this surface meaning there is a secret assumption. The advertisement has surreptitiously rested its hand on the spigot of our enjoyment, telling us when and when not to enjoy, assuming the burden of answering a difficult philosophical question: What do I enjoy and how long do I go about enjoying? (Coke’s answer: If you have bought a Coke, then go ahead and enjoy! If not, then don’t enjoy.) And we are all used to experiencing the sort of mindless joy (which secretly conceals an abysmal emptiness) that accompanies buying anything; when pleasure, permission, and happiness are, for a fleeting moment, determined not by our own mind, but mediated by the purchase.

Industrialized economies of wealthy nations like the United States, having fulfilled the basic needs of their citizens, have now turned from manufacturing things they didn’t need to, in effect, manufacturing need.

These critiques came from leftist cultural critics like Charles Reich and Marcuse, but also conservatives such as Catholic political commentator Reinhold Niebuhr and liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith. All warned that if America did not stop producing tremendous waste and absurd new visions of what was considered affluent to sell, the country would eventually become a nightmarish version of itself, in which the fabric of its values and communities (not to mention its public services) would tear under the weight of industrial marketing.

As Marcuse put it, after “true needs” such as “nourishment, clothing, and lodging at the attainable level of culture” were met, the industrial engines that generated these goods didn’t simply shutter their factories and declare their jobs done. Instead, they discovered it was far more profitable to simply generate false needs by convincing people “to relax, to have fun, to behave and consume in accordance with the advertisements, to love and hate what others love and hate.”

When we enter high-end, hippie-themed stores like Whole Foods, we hear a pastiche of counterculture anthems—The Doors, The Ramones, The Clash, disembodied voices from different eras all growling angrily about the way society is structured—piped in to convince us to let loose and enjoy ten-dollar teas.

When punk emerged in the 1970s, it was a porcupine, literally armored and covered in spikes. Unlike the welcoming hippies, it appeared to be designed to resist being swallowed up. It embraced everything mainstream culture wasn’t: anything ragged, filthy, offensive, brutal, disgusting, or weird. For this purpose—just as 4chan would later—it adopted Nazi imagery in an attempt to shrug off co-optation.

Nirvana is a sad example of this nouveau punk. The band’s front man, Kurt Cobain, wore ratty sweaters and never washed his hair. He told his fans he hated his life as a rock star, the TV that promoted him, and the record label that sold his music. His breakout album depicted a baby swimming after a dollar baited onto a fishhook on its cover and struck a chord with how kids felt, innocents tugged in all directions by consumerist desires. Promised a commodified, transcendent nirvana, this new generation instead felt indifferent, as the album’s wobbly title Nevermind asserted. Eventually, Cobain blew his brains out, a final insistent act to prove that he was genuine, that he truly did despise his role in the whole affair.

In the early 80s, the first VCRs and PCs began to be sold with yet another innovation in marketing: corporations found they could aim their advertisements at very young children. Cartoons, computer games, films, TV shows, and other media were produced to sell the new material plastic, which, if imprinted with the fantasy of intellectual property, could be moved at a tremendous markup.

Technological innovations still occur every day, but they often seem more menacing than helpful. Most inventions are no longer regarded as a step toward some better world. Rather, they are often read as yet another minor herald of inequality and apocalyptic disasters (via global warming, new wars, etc.). Even the most prominent examples of “progress,” like smartphones, are generally employed as ways to disappear, to distract and remove ourselves from an increasingly unhappy reality.

The hippies produced cultural “victories” like long hair and casual office environments, but their larger goal of using new technology to radically alter the structure of postwar capitalist society was never realized.

By the early 2000s, music had become endless techno remixes of past genres. Film evoked 80s and 90s vibes, and the future, whatever it was, resembled the digital loops of film and music, old styles, old clothes, old feelings on shuffled repeat.

By the 90s, it seemed to many that time had gone off track somewhere. This was the theme of leftist philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s 1991 riposte to Fukuyama, The Illusion of the End, and Jacques Derrida’s 1993 Specters of Marx.

A new meme called the “Mandela Effect” joked that perhaps we really had “skipped timelines” and time was literally out of joint. Message boards became obsessed with the idea that misremembered childhood memories (such as the commonly held but erroneous belief that revolutionary South African emancipator Nelson Mandela had died in jail in the 90s) meant that a time traveler had fiddled with the past and we were living in a glitch.

Shortly after Trump ascended to the presidency, the conservative blogger Milo Yiannopoulos attempted to visit Berkeley’s Sproul Hall to give a speech. The talk was part of what he labeled his “Dangerous Faggot Tour,” an allusion to his homosexuality, but also the font of his rhetoric, 4chan, whose users referred to each other as “faggots.”

Now that Trump had taken office, tensions boiled over. At his previous speech at the University of Washington, one of Yiannopoulos’ supporters had attempted to murder a counterprotester, possibly in response to the clashes that had occurred between far-right and far-left protesters on inauguration day. And so, as Yiannopoulos approached Berkeley, hundreds of faculty, staff, and students sought to bar him from entering.

The Matrix was inspired by the works of Jean Baudrillard. (In an early scene, Neo stores his hacking materials in a hollowed-out copy of Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation.) But Baudrillard condemned the film, saying, “The Matrix is the sort of movie the Matrix would make.” By this he meant that The Matrix exploited the longing of a generation to liberate themselves from the paralysis of the screen to sell yet another escapist screen illusion, a kung fu action movie. The Matrix expressed a duality: On the surface it conveyed Baudrillard’s revolutionary message of using technology to shatter the oppressive technological control systems. But secretly, it proclaimed the opposite, suggesting that people dive further into screen illusions. The underlying ideology of the film was that reality was fake and the screen was real. In other words, it used people’s longing to be effective in the real world to advocate escapism.

In another book that defined 60s counterculture, the 1970 Greening of America, a Yale Law School professor named Charles Reich argued that technological advances were not generating increasing autonomy and individual freedom.11 Instead, they were creating a vast cooperative power hierarchy split between corporations and government bureaucracies. Even the people at the top, the politicians and CEOs of companies, had little power to change the interlinked, hyper-logical system. Reich called this the “Corporate State.”

In the mid-70s, Loving Grace Cybernetics transitioned into the Homebrew Computer Club, an effort by Felsenstein and others to make computers and communications networks “personal,” out of which the first PCs and modems emerged, most notably Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak’s Apple computer.

During the 70s, the internet was a network of university research computers called ARPANET, on which personal discussions were forbidden. But running parallel to the hippie hacker scene in the Bay Area, corporations like Xerox, universities, and quasi-government corporate institutions like Bell Labs were also developing PCs and network protocols. And in 1979, two young academics working in this field, Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis, invented a “poor man’s ARPANET” called Usenet, which could be accessed via a modem and the new PCs. Soon, Usenet looked much like the message boards of today, except they were, of course, text-based. Users subscribed to different news groups and commented on threads on topics ranging from cooking to space exploration.

Famously, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had been part of the phone phreaks hacker scene in San Francisco and acquaintances of Don “Captain Crunch” Draper, who had discovered that the toy whistle in cereal boxes replicated the exact tone that convinced a payphone a line was open (2,600 MHz), thus earning the whistleblower free access to the phone company’s network. Draper had also been part of the Homebrew Computer Club.

A new generation of practicing hackers who defined themselves by their capacity to understand systems and break into them: Eric Corley, under his pseudonym “Emmanuel Goldstein” (the name of the radical enemy of the government in 1984), who published 2600: The Hacker Quarterly (named after Draper’s 2,600 MHz), and two teenage members of a New York City–based hacking group, Mark “Phiber Optik” Abene and Elias “Acid Phreak” Ladopoulos.

To Felsenstein, quoting Ginsberg, hackers were “burning for the ancient heavenly connection.” They went “where artists go,” to the “Epsilon-wide crack between What Is and What Could Be.”19 And they had largely accomplished their goal. They had liberated computers from large institutions and turned them into tools for creative expression. “We cracked the egg out from under the Computer Priesthood,” he wrote, “and now everyone can have omelets.”

Otaku were extremists. But their culture, obsessive fan interest in products and escapist fantasy worlds, was growing in the hearts of the broader population. In addition, many Japanese visiting the web for the first time reveled in the anonymity. They too found relief in escaping Japan’s strict hierarchy of polite deference. Unlike the hyper-polite real world, people found they could be rude to one another with impunity.

In appearance, 2channel is remarkable not for its chic elegance, but for a messiness that characterizes its design. It’s a set of maddeningly unaligned pastel boxes with plain text interspersed and other items piled up chockablock in the corners of the screen. Nishimura, like his design sensibility, was shockingly breezy, sloppy, and indifferent in a society that prized none of those things, or at least, not previously.

Like the young otaku in Japan, Lowtax occupied a cubicle in a vast, impersonal bureaucracy. Unhappy, he retreated to games and online networks. But unlike the otaku, Lowtax did not aspire to enter the game and lose himself in the experience. His attitude typified the American response to the same problem, informed by a counterculture that had spent decades battling corporate co-optation. He knew the fantasy worlds sucked too. And the best defense he could muster against them was unrelenting mockery.

As a young man in the shadow of corporate culture, he did not see the internet as a network that would bring about a transcendent way of doing business and communicating. Rather, he intuited the common truth of his generation: that he was living in a psychic garbage dump.

Around the same time that Nishimura created 2channel in Japan, Lowtax founded a site he called Something Awful (SA). It was a name he plucked out of nothing, specifically the nothing of the fast food–littered suburbs, a phrase he simply uttered all the time, as in “that Del Taco burrito sure is something awful.”

A long time ago, if somebody said they really wanted to fuck a pillow with anime on it, if they went out in public and said that, they would be laughed at. There would be some element of shame. They would keep that inside and say, “Well, I want to fuck a pillow with anime on it but I can’t tell anybody.” But then the internet came along and they could get on a webring or whatever it was back in the day. Go to rec/all/fuckanimepillow or whatever. Then other people would say “I want to fuck anime pillows, too.” You had this community of people who were very intent on fucking anime pillows. The typical person does not want to fuck a pillow with anime on it. This, of course, was back when fucking anime pillows was fresh and new.

I found it to be very interesting that these subcommunities would sprout up and their numbers would grow and pretty soon it’s Pillowfuckers United, Inc. And I found that whole process back then—it was even happening in the usegroup days—I found that whole process incredibly interesting, how the groupthink would manifest itself and increase exponentially over time.

SA forums encouraged exactly what moderators elsewhere took great care to eradicate: bile, cynicism, cruelty, mockery, and vulgarity.

Another constraint that 4chan abandoned was common decency. Libertine and experimental as it was, SA had a set of rules. And Lowtax had no compunction about drawing a clear moral line regarding what he would tolerate on his site. In fact, he delighted in purging users and content he found contemptible.

He set most of the rules next to the outer bounds of the rules that already existed, that is to say, the law. As he later phrased it, he was allowing 4chan’s community “to define itself.” But it was something only a shrugging teen boy would do, one who had not yet worked out his own value system and, as most adolescents do, was experimentally mirroring the culture around him, in this case, one of competitive transgression. As Lowtax described it to me, “4chan was like a race to see who could be the most crazy, fucked-up piece of shit possible. And they were all winning.”

The ironically named Anime Death Tentacle Rape Whorehouse signaled to genuine fans of tentacle rape that such content was tolerated there, even if the original intention was to mock anime. 4chan’s early userbase was born from one of these ADTRW purges, which SA called “the pedocaust.” Or, as Lowtax told me, “I was tired of trying to figure out whether this sexualized drawing someone posted depicted an eleven-year-old girl or a 500-YEAR-OLD WITCH from princess whatever-the-fuck volume fifty-six.”

Though 4chan would soon spawn communities of hackers and trolls who would come to define much of the present internet, the core of its culture remained in Japanese cartoons and fetish porn.

Herbert Marcuse argued that by the mid-twentieth century, people’s understanding of the world had been fractured in two: a literal-minded deterministic view of reality (as dictated by the authority of experts and scientists), which closed off imaginative possibilities of better futures (personal or political); and an indulgent, outlandish fantasy life regarded as totally unreal.

In our twentieth- and twenty-first-century romantic fiction, super-effective heroes change not just their own lives but the entire world for the better. They are not simply more adventurous than us, but commune with transcendence itself in intergalactic Hollywood “infinity wars.” To the nineteenth-century Romantics who invented this genre of storytelling (and the countercultures that followed), possibility, imagination, transcendence, heroic action, and creativity were internal qualities employed as tools to interpret the real world.

The first American articles about otaku worshipping overpackaged young Japanese idol singers framed the phenomenon as a case of Japanese extremism that was considered far too distasteful to ever occur in the United States. But within a few years, the idol phenomenon arrived with performers like Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, and Miley Cyrus.

Japanese extremism was often the subject of mockery in the United States. Easterners, it was imagined, had a tradition of obsequious subservience to the hierarchy of Confucianism. Americans laughed at how Japanese people debased themselves on humiliating game shows in ways that seemed unthinkable to someone possessed of the inviolate dignity of the Western individual.

To understand what the word “meme” means, it’s helpful to learn its origins. Biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term in his 1979 book The Selfish Gene as part of an argument reframing how we think about evolution. The central idea of The Selfish Gene shifted the focus of Darwin’s competition for survival from the individual organism to the genes of that organism, the instructions that produce all its traits, from the shape of its eyes to its behavior.

Evolution was often better understood, Dawkins argued, not as a struggle for the organism’s survival, but for its genes to replicate themselves at the expense of other genes. For example, Dawkins suggested his paradigm more fully accounted for why animals often defend or feed their offspring or siblings to their own detriment.

There’s not much of a difference between a gene and an abstract idea. A gene is simply a way to store bits of information (eye color or an imperative to cooperate, etc.). Dawkins’ next point was that we can imagine a set of genes that are simply ideas. They don’t have a physical form, but they still replicate themselves over and over in an evolutionary struggle for our attention. These are memes.

Technically, internet memes were invented on Something Awful (SA), where the first image macros (funny pictures captioned with white impact font) appeared, because there, too, people gathered not to exchange ideas but to compete to be funny. But around the same time 4chan was founded, Lowtax banned the practice, believing that simply copying someone else’s joke and changing it slightly wasn’t all that creative.

Like memes, trolls had been knocking around the internet for years, but they only began to coalesce as a distinct phenomenon on SA and then 4chan. The term was derived from both the cranky creature sitting underneath the bridge disrupting the flow of traffic and a fishing practice in which chum is thrown into the water to attract fish.

Though most of 4chan’s trolls were anonymous, we know a great deal about one of them. Andrew “weev” Auernheimer embodied each of 4chan’s historical transformations: from meme creator, to troll, to hacktivist, then, finally, to neo-Nazi figurehead of the alt-right.

the internet.10 Auernheimer and his circle of friends called themselves the Gay Nigger Association of America (GNAA) and recruited by advertising on content-aggregating sites like Slashdot. Initiates were required to watch the short film Gayniggers from Outer Space and answer questions about it.

The other trolling collectives on SA and 4chan would later adopt this practice, often referring to themselves, with a mixture of racism and envy, as “nigras.”

Anonymous had chosen the radical V from V for Vendetta as their symbol because of the movie’s revolutionary overtones. In both the 2005 film by the Wachowski siblings and the 1989 comic book upon which the film is based, V is an anarchist bomber fighting against a future fascist Britain that has beaten its populace into indifferent submission. But V was also selected because he resembled the typical anon, a scarred weirdo, unable to remove his mask, but witty and sophisticated.

Like everything on 4chan, the project grew in complexity as it was crowdsourced. For example, the second edition of the wiki began: “The Return of the Well Cultured Anonymous is an updated book, based on the original Well Cultured Anonymous… It attempts to show others (primarily other Anonymous) how to be sophisticated, talented, and polite in today’s modern world.”

Chapters offered instructions on how to self-improve not just in the real world, but in the more difficult terrain of your own mind. In a section titled “Why bother?” anons explained to other anons the trap of false pride that occurs in dwelling in virtual accomplishments like video games. “It’s one thing to beat all your mates at Mario Kart even though they always seem to get blue shells on the last lap. That may feel good temporarily, but you’ll know that most people IRL don’t give a shit so you won’t feel proud of it.”

As “cablegate” progressed, a group of high-level former CIA, FBI, and government analysts, including the Pentagon Papers whistleblower, Daniel Ellsberg, issued a joint statement, writing that the old Russian propaganda paper Pravda was reporting on WikiLeaks better than Western media. “The corporate-and-government-dominated media are apprehensive over the challenge that WikiLeaks presents.” They cited Pravda’s sentiment that “what WikiLeaks has done is make people understand why so many Americans are politically apathetic… After all, the evils committed by those in power can be suffocating, and the sense of powerlessness that erupts can be paralyzing, especially when… government evildoers almost always get away with their crimes.”

In March 2018, a former employee of Cambridge Analytica named Christopher Wylie revealed that the company had used a quiz app to scrape data about millions of people off Facebook in 2014 without their permission to build “psychometric profiles” of voters in the United States and Britain. They then used those profiles to manipulate votes.

Thiel would attribute his decision to invest in Facebook to his study of the philosopher René Girard, who posited that human beings define themselves by observing and copying others. But another, far more down-to-earth explanation exists. A few months earlier, Thiel had received funding from the CIA’s venture capital arm to start Palantir. Palantir would profit (immensely) from acquiring as much data as possible about people and selling it to large institutions, mostly the government and law enforcement. According to internal documents leaked by TechCrunch in 2015, “as of 2013, Palantir was used by at least 12 groups within the US Government including the CIA, DHS, NSA, FBI, the CDC, the Marine Corps, the Air Force, Special Operations Command, West Point, the Joint IED-defeat organization and Allies, the Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.”

It seems likely that Thiel saw in Facebook another opportunity like Palantir— a way to collect, analyze, and sell large data sets.

Partly, Anonymous dressed itself up like V because V for Vendetta was a meditation on this post-9/11 erosion of privacy.

As a society of ribald boys, 4chan had always been obsessed with masculine competition (and the subsequent humiliation when the contest was lost). The popular slang “epic win” and “fail” were 4chan inventions.

In The Matrix, the world of the screen attacks the legitimacy of the real world, condemning it as fake and suggesting its illegitimacy can be transcended through tremendous acts of violence, a deeply evocative message for a generation whose feelings were undermined by the hyper-real world of escapism.

The PUA movement, popularized by a reality TV show and bestselling book, taught romantically unsuccessful men a cookbook-style method for picking up women. Like 4chan’s culture, PUA told betas that they could ensnare women with a generous application of sociopathic manipulation.

Though people often regard fascism as meaning something like “the state owns the means of production,” this definition is nowhere close to the scholarly consensus on the subject.3 While the exact meaning is hotly debated, there are several general markers upon which everyone agrees: Fascism is enamored of authoritarianism and a rigid code of “traditional” values that belongs to an ideal age in the past.

A clear definition of fascism has remained obscure because both left and right attribute its rise to the other side of the political spectrum. The first appearance of fascism in the 1930s coincided with a resurgence of socialism, which caused some on the right, perhaps most famously the economist F. A. Hayek, to attribute fascism to the specter of socialism.

In the United States, as well as in Europe, economically liberal capitalism has disenfranchised so many people that they have begun to search for alternatives to the status quo in socialism and fascism. All under the threat of being reduced, as Hayek puts it, to “serfdom.”4 From our contemporary viewpoint, it appears far more likely that radical political alternatives to Western liberalism have appeared because we have reached levels of economic inequality comparable to the 1920s and 30s.

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, the philosopher Hannah Arendt argues that fascism, when it first appeared in the 1930s, was generated by the conflict between Enlightenment values and industrial capitalism, in particular a feeling of total powerlessness that industrial capitalism produced in Enlightenment societies.

As society structured itself around its prodigious ability to produce factory-made products, human beings began to regard themselves as inherently acquisitive beings whose very nature was bent toward nihilistic accumulation.

Arendt described how, in the 1930s, groups of dispossessed people from the lower, middle, and upper classes all began to aspire to the cruel-minded values of a certain type of businessman who, like Trump today, was “flattered at being called a power-thirsty animal.”11 It was this social Darwinist viewpoint that made the industrialist Dale Carnegie’s 1936 self-help book How to Win Friends and Influence People a bestseller. His ideological outlook flattened relationships among people into a businesslike game of hierarchy and acquisition similar to contemporary bestsellers like The 48 Laws of Power. (“Law 2: Never put too much trust in friends, learn how to use enemies.” “Law 7: Get others to do the work for you, but always take the credit.”)

After World War II, both the Republican and Democratic parties in the United States have been uniformly “liberal,” in the economic sense. They only disagree on the degree to which the state should regulate capitalism. And now, in the twenty-first century, when inequality has reached levels only previously attained in the late 1920s, youth movements have once again emerged outside this narrow band of political thought.

#gamergate was a self-described gamer revolt on 4chan that ended up briefly breaking the games industry and, a few years later, American politics indefinitely.

Depression Quest was part of a new wave of avant-garde indie titles that broke out of the narrow confines of puerile subject matter and reconfigured old tropes to deal with a broader spectrum of subjects.

When Pepe memes exploded into the thousands in 2015, this in and of itself became a meme as users pretended to stockpile “rare” images of Pepe as they might collect gems or stamps. Robots placed USB drives full of Pepes up for sale on eBay.

The 4chan meme “doge,” a cute, clueless Shiba Inu, already enjoyed his own virtual security—Dogecoin. And eventually, alt-coin PepeCash would power art auctions of rare Pepes using blockchain. And this, in turn, would fuel the viral success of a man claiming to have made a fortune trading Pepe crypto, “PepeCashMillionaire,” as he came to be known on Twitter and Instagram.

Jacobus didn’t understand anything about 4chan, /pol/, or even gamergate, but she saw that Pepe appeared frequently in the nasty comments from young Trump supporters that appended her tweets. “The green frog symbol is what white supremacists use in their propaganda. U don’t want to go there,” she tweeted at a colleague.

Within an hour of Jacobus’ Pepe tweet, someone had posted it to /pol/. And to /pol/ocks, the next step seemed obvious. They wanted to make the connection real, and so they began flooding Jacobus with the most offensive, racist, and pro-Trump Pepe memes they could scrape from the bottom of the chans: Trump-loving Pepes gripping assault rifles; Pepes with swastikas on their foreheads, Manson-style; smug Pepes in yarmulkes watching the twin towers fall.

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt carefully traces the font of such ideas and their relationship to race-based thinking through the Comte de Gobineau and Oswald Spengler.

The same dynamics occurring on Tumblr are perhaps best shown in its relationship to an episode of the dystopian science-fiction TV series Black Mirror titled “San Junipero.” In the piece, a young interracial couple fall in love in a montage of hyper-real retro settings, pitch-perfect replications of the glamorous backdrops from classic movies of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. And here’s the twist (spoiler alert!): they are meeting in a networked virtual reality simulation. Though they appear as teenagers, in real life they are very old and using the fantasy realm to explore their sexuality in ways that were not possible in their own lives. The story ends when the two lovers, facing death, upload a copy of their consciousness into the simulation. There, the computer replicas of their brains endure together forever, dancing and partying in paradise.

What counterculture emerged after the punk disaffection of the 90s? In retrospect, it seems almost inevitable: an endless, neurotic labeling project. Counterculture, after numerous escape attempts, was still in the same prison. And now the prisoners had become a little unhinged. For decades they had tried to gnaw their way through their chains. Now they began to gnaw on themselves. The new generation focused on cataloging all the ways they felt impotent.

In an uncertain world, what could be a worse anchor than what philosophers like Judith Butler discarded as so fluid it was meaningless—identity?

At the core of both youth cultures was the disease of the twenty-first century: depression and anxiety. Fisher’s book was about how depression was better regarded as a cultural malaise than an individual sickness.

“I learned women want to be downright abused,” he opined in an interview. “When I stopped playing nice and began totally defiling the women I slept with, the number of them willing to sleep with me went through the roof.” But unlike among the pickup artists (PUAs), women were not the focus of the Proud Boys; boys and pride were.

in a nod to the dissipation of media and the internet that had brought so much of Yiannopoulos’ fan base into being, McInnes imposed the ultimate patriarchal injunction upon his boys: no masturbating more than once a week. A man’s vital energy, he argued, was better spent trying to free oneself from indulgent fantasy. Proud Boys needed to step out into the real world and attain women in the flesh.

Clinton’s campaign released a statement condemning Pepe the Frog. In what The Verge called the “death of explainers,” Clinton’s team described how Pepe, “an innocent meme enjoyed by teenagers and pop stars alike,” was now a hate symbol. To young people, the idea that Pepe, the symbol of idiotic internet trash, now took center stage in U.S. election coverage only confirmed their suspicion that the whole affair was so much tawdry refuse.

Our “boring dystopia,” as Mark Fisher called it, is a far cry from H. G. Wells’ postwar utopia in The World Set Free. But it does resemble Aldous Huxley’s parody of the book, Brave New World, in which instruments of liberation are freely available to future citizens. But, distracted by shallow entertainment, few care to employ them. For the first time in history, a better world seems out of reach not for technological reasons but for political ones. Absurdly, we all think we’re going to die when civilization collapses because we can’t imagine everyone acting better.