Digital Minimalism

I’m vulnerable to digital distractions and you probably are too. Here’s a book which analyzes the problem and offers guidance on improvement.

Through living and traveling overseas for over ten years, I’ve become more and more enamored with a minimalist lifestyle. There are countless blog and podcasts explore subjects of practical minimalism like reducing clutter, ultralight travel, and identifying the things which matter to you most. And they help a lot, but there was one phenomenon in particular which this book addresses, and that is the natural attraction that most of us feel toward screens and information. The most common manifestation of this is through the device which we have with us at all times: smartphones.

Although people habitually peering at their phones throughout the day is a global phenomenon, I sense that it might be even more entrenched in China than in other places. China is ahead of the rest of the world in leveraging the smartphone to become the universal enabler of modern life. In a single day people in China use their phones to communicate with friends and family, pay for virtually everything from vegetables to a movie, call a car or order food delivery, and much more. It’s so convenient that there’s an unmistakable magnetic effect, which might lead you to wonder: is there a downside to this kind of digital lifestyle?“

“Few want to spend so much time online, but these tools have a way of cultivating behavioral addictions. The urge to check Twitter of refresh Reddit becomes a nervous twitch that shatters uninterrupted time into shards too small to support the presence necessary for an intentional life.”

Unfortunately, for most people eliminating some of these tools will be difficult or impossible. With that in mind, what are the real effects of our modern digital lifestyle and what practices should we encourage to promote health and happiness? These are the questions which Digital Minimalism asks and seeks to answer.

Effects of the “Like” Button

One of the most profound concepts in the book is the deep psychological impact that the “Like” button (on Facebook and other social media platforms) has on our behavior. Since the 1970’s scientists have determined that rewards delivered unpredictably are far more enticing than those delivered with a known pattern. Something about the unpredictability of rewards, like seeing how many people liked a post, releases more of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which regulates our sense of craving.

“Leah Pearlman, who was a product manager at Facebook on the team that developed the “Like” button for Facebook (she was the author of the blog post announcing the feature in 2009), has become so wary of the havoc it causes that now, as a small business owner, she hires a social media manager to handle her Facebook account so she can avoid exposure to the service’s manipulation of the human social drive.”

Rather than just a digital conduit through which we’re connected with friends, Facebook and its peers can also be viewed as a psychological trap designed to target our deep-seated vulnerabilities with staggering precision and efficiency. We’re unprepared to use these tools in a way which suits us best because we are subject to the whim of experts whom often know us better than we know ourselves.

“The “Like” feature evolved to become the foundation on which Facebook rebuilt itself from a fun amusement that people occasionally checked, to a digital slot machine that began to dominate its users’ time and attention. This button introduced a rich new stream of social approval indicators that arrive in an unpredictable fashion—creating an almost impossibly appealing impulse to keep checking your account. It also provided Facebook much more detailed information on your preferences, allowing their machine-learning algorithms to digest your humanity into statistical slivers that could then be mined to push you toward targeted ads and stickier content.”

Usage of the Like button seems like an innocuous interaction, but over time it teaches your mind that connection is a suitable alternative to conversation. Despite our best intentions, the role of these low-value interactions rapidly expand to push out high-value socializing.

Since reading this book and learning more about this effect, I have stopped clicking the Like button. As the author of the book states in clear terms: “Don’t click Like. Ever.”

Reducing Social Media

A trend which I first observed in 2017 has been friends deleting social media accounts, particularly Facebook. This is partly due to a generalized feeling of Facebook being an unessential distraction, but it’s more than just that. Many were prompted to more deeply consider Facebook when founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg was interviewed by the U.S. congress about Facebook’s role in the 2016 presidential election. Since then, I’ve noticed at least a dozen friends delete their Facebook accounts. And while I haven’t deleted mine outright because it’s my only social connection to family members abroad, decluttering low-value digital distractions on social media has become a priority.

Remove people who aren’t your friends from your friends list. Acquaintances you might never see or speak to again don’t count as friends. Despite what Facebook would lead you to believe, no one really has 1,000 friends, or even 200 friends (an instructive scientific study on the theoretical social limits of human friendships is called Dunbar’s Number, which states that our brains aren’t capable of keeping tracking of more than 150 people in our social circles).

Focusing on Intentionality

The prescription which this book offers to navigating the digital landscape of distractions and rabbit holes is this: focus your online time to a small number of carefully selected activities that support the things you value, and skip everything else.

This is in direct opposition to the “maximalist” approach deployed by most by default, where any potential benefit is enough to start using an app or technology that catches your attention. It comes from a scarcity mindset, or a fear that there’s something useful you’ll miss out on, but this book encourages a fear of the opposite. Not missing the small things, but diminishing the large things that we already know give us great value.

“Thoreau establishes early in Walden: “The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.”

The cumulative effect of unessential distractions accumulate to outweigh the price that we pay for them: time we won’t get back.

Online vs Offline Interactions

Online interactions with friends and family generally occur on a narrow band of information: a like, a comment, or a short message. By comparison, offline interactions are rich and occur on a broad band because we utilize massive neuronal power to deduce what’s happening in a face to face social situation. It’s through millions of years of evolution that we perform complicated computational feats in social situations without thinking about it.

An example which the author of the book uses to demonstrate this phenomenon is competitive Rock Paper Scissors players.

“A strong Rock Paper Scissors player integrates a rich stream of information about their opponent’s body language and recent plays to help approximate their opponent’s mental state and therefore make an educated guess about the next play. These players will also use subtle movements and phrases to prime their opponent to think about a certain play.

Understanding Rock Paper Scissors champions is important to our purposes because their strategies highlight a foundational endowment shared by every human being on earth: the ability to perform complicated social thinking.”

Making Optimizations

A few optimizations are encouraged in the book, some of which I’ve put into practice and found effective.

- Don’t watch television or movies alone. This restriction allows you to still enjoy these things, but in a more controlled manner that limits their potential for abuse while strengthening social bonds at the same time.

- Remove social media apps from your phone. You can still access these services from your computer browser when you need, but you might find that you won’t bother much, because they won’t be accessible as a knee-jerk response to boredom.

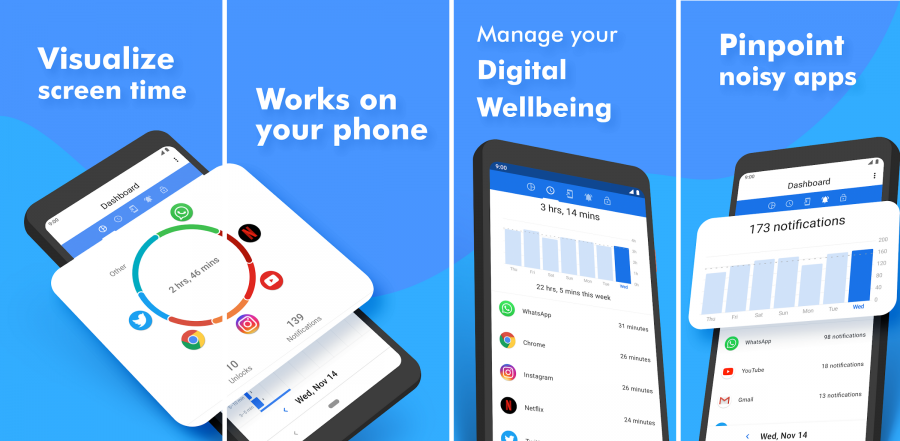

- Track time on your phone and computer, evaluate the data, and make judgements on how to best spend your time. More details on this below.

Time Tracking

Over the last year both iOS (Apple) and Android (Google) have deployed time tracking utilities on their smartphone platforms specifically for the purpose of observing usage patterns. Apple calls this Screen Time and Google calls it Digital Wellbeing, but they do the same thing: they inform you of how much time you’re spending on your phone, and which apps occupy you the most (note: there are alternative apps available also, like the one I’m using which is ActionDash – it has Digital Wellbeing’s functionality plus much more).

The results of tracking your phone usage will probably shock you: almost all of us spend much more time looking at our phones than we realize. For many this is a great first step. Track time on your phone first, and then on your laptop. Two tools which I’ve used and can recommend for time and app tracking are Qbserve (Mac) and Rescue Time (Windows & Mac).

If you’re interested in hearing the principles of this book explained in a podcast, this is a good episode with the author of the book featured as a guest on The Minimalists podcast.

Unlike smoking or drinking alcohol, the negative effects of digital distractions are less apparent. Instead of killing you or making you sick, they consume countless small fragments of time, which cumulatively have a hampering effect. Identify, target, and eliminate these and you’ll be better off.

- View all of my highlights from Digital Minimalism

- Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport on Amazon